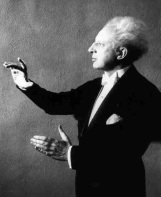

Stokowski

The story of Toni’s “discovery” by Leopold Stokowski might seem to belong in the folklore category, but this is how she told it, short and sweet. He saw her playing cimbalom in a nightclub, stood up with his famous white mane streaming behind him and, as if on the conductor’s podium, pointed at her and said “You!”

Back when conductors were larger than life, Stokowski had extended his hand to Mickey Mouse, a gesture that famously inflamed purists. The result was “Fantasia,” which probably assured his immortality. He would now put the wheels in motion that would rescue an little-known instrument’s endangered repertoire and insure it a bit of immortality as well.

His plan was to record an album with Toni called “Rhapsody,“ which would include Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies 1,2, and 3 and Enesco’s Roumanian Rhapsodies 1 and 2. Stokowski added the cimbalom to the original orchestrations for these recordings. (Liszt had used the cimbalom in his 6th Rhapsody only. Enesco had an affinity for the cimbalom, but it seems he did not write for it.)

Soon after working with Stokowski she received a call to perform Bartok’s First Rhapsody with the great violinist Josef Szigeti (the composer had dedicated this work to Szigeti) and conductor Tibor Serly, at a concert at Columbia University commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Composer’s death. Almost immediately she received calls to perform Kodaly’s Hary Janos with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony and with Dimitri Mitropoulos and the New York Philharmonic. The calls continued to come. The original cimbalom part in this colorful work, usually played by a piano, would now be played as written.

Toni took all of this on never having played with a symphony orchestra (which at that time rarely if ever saw a woman in the pit) or had anything like a formal music education, wrestled with a score, been in a recording studio, partnered with a violinist of Szegiti's stature or worked with a conductor.

She had begun an unanticipated and extraordinary chapter in her career.

Back when conductors were larger than life, Stokowski had extended his hand to Mickey Mouse, a gesture that famously inflamed purists. The result was “Fantasia,” which probably assured his immortality. He would now put the wheels in motion that would rescue an little-known instrument’s endangered repertoire and insure it a bit of immortality as well.

His plan was to record an album with Toni called “Rhapsody,“ which would include Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies 1,2, and 3 and Enesco’s Roumanian Rhapsodies 1 and 2. Stokowski added the cimbalom to the original orchestrations for these recordings. (Liszt had used the cimbalom in his 6th Rhapsody only. Enesco had an affinity for the cimbalom, but it seems he did not write for it.)

Soon after working with Stokowski she received a call to perform Bartok’s First Rhapsody with the great violinist Josef Szigeti (the composer had dedicated this work to Szigeti) and conductor Tibor Serly, at a concert at Columbia University commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Composer’s death. Almost immediately she received calls to perform Kodaly’s Hary Janos with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony and with Dimitri Mitropoulos and the New York Philharmonic. The calls continued to come. The original cimbalom part in this colorful work, usually played by a piano, would now be played as written.

Toni took all of this on never having played with a symphony orchestra (which at that time rarely if ever saw a woman in the pit) or had anything like a formal music education, wrestled with a score, been in a recording studio, partnered with a violinist of Szegiti's stature or worked with a conductor.

She had begun an unanticipated and extraordinary chapter in her career.